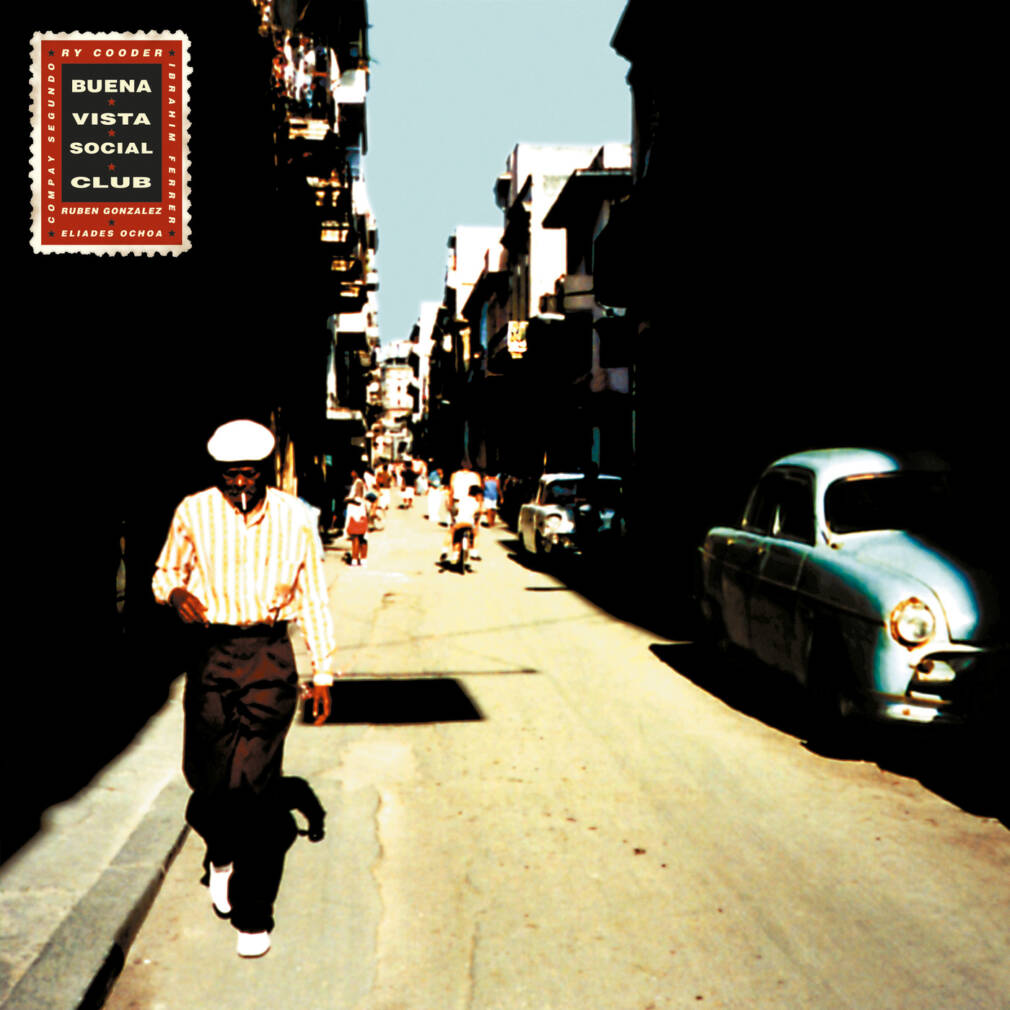

It was in March 1996. British producer Nick Gold was flying to Havana and had booked the legendary Egrem studio, which had seen so many Cuban music heroes pass through since the 1940s. Soon he would be joined by Ry Cooder, the American guitarist who had recorded the famous Talking Timbuktu with Ali Farka Touré, which won a Grammy Award in 1994. With the original plan of building a musical bridge between Cuba and Africa, he had no idea that he was about to make the album of his life, and change the lives of all those involved. The record, which would be called Buena Vista Social Club, would sell more than eight million copies and successfully put Cuba back on the world music map for a long time.

Today, as the label reissues this mythical album, Nick Gold tells us the story, made up of small miracles and equally as much chance, talent, feeling, and good vista.

After having produced African artists such as Ali Farka Toure or Cheikh Lo, how did you get involved into Cuban music?

Well, I had heard bits of Cuban music, but not a lot, when – it was in 1986- Ann and Mary (founders of World Circuit) brought over from Cuba a singer called Celina Gonzalez. She did country music, but not like American country music, but rural Cuban music… and she was fantastic! We licensed the record from Egrem, the Cuban state company, and anyway I enjoyed that very much and started to listen to bits of Cuban music and I just fell in love with two records by Arsenio Rodriguez, a Cuban musician that became very important in the 1940s. And then, when I started working with Ali, as I first started going to Mali, you heard Cuban music a lot. Especially in Bamako, in bars and so forth. And maybe the first African record I completely fell in love with was an Orchestra Baobab record, which we eventually found and released later (in 2001) as Pirate’s Choice. This record had very strong Cuban influences on it.

So it was this powerful connection that Africans had with Cuban Music that led you to the Buena Vista idea?

Yeah, absolutely. It was hearing the popularity of Cuban music when I was in Africa and also, that West-Africans seem to like the same sort of Cuban music I liked!

How did you get to Buena Vista?

I knew Bassekou Kouyaté and Djelimady Tounkara, and I think I’d heard Djelimady do Cuban style recordings. In Celina Gonzalez’s band, there was a musician called Barbarito Torres, and I just had an idea that bringing those musicians together might be interesting. At that time, I’d also started to understand a bit more about which Cuban music I liked : Guillermo Portabales, Abelardo Baroso, so a lot of music from the East (the Santiago area). I’d also met by this time Eliades Ochoa, via Lucy Duran (she’s a musicologist in London) and also Mary Farquharson who was the original founder of World Circuit. Eliades, Barbarito, Djelimady and Bassekou : I thought that combination would somehow be interesting to do, and then around this time, I met a band called Sierra Maestra, who’s like a Havana based band playing traditional son music. I was talking with their leader, Juan de Marcos Gonzalez about various recordings. And both of us loved Arsenio Rodriguez. And he was saying “okay, a lot of Arsenio’s musicians are still alive and playing in Havana, including Ruben Gonzales, the pianist”. So he had this dream of making a bigger band record, a multigenerational tribute to this music. So I thought “okay, if he’s doing that and I’ve got this idea, maybe we can try both”. So we decided to make these 2 records, one of a big multigenerational band doing more Havana-based music, and then a Santiago more acoustic guitar-based music recording. And then soon before we left, I asked RY Cooder if he wanted to come. And he immediately came back and said yes. So I booked the studio for 2 weeks, got Djelimady’s flights, Bassekou’s flight, booked Barbarito, and the rest of it would be sorted when we’d get there. And just before departure, we heard that Basekou and Djelimady couldn’t come. There are various stories of why they couldn’t come. What we heard at the time was that their passports was sent to Ouagadougou to get their Cuban visas but didn’t get back in time. But weirdly enough they didn’t need visas because there were cooperations between Mali and Cuba, anyway we found out after. So I said to Ry “look, the Africans can’t come”. And he said “Let’s just try something when we get there”.

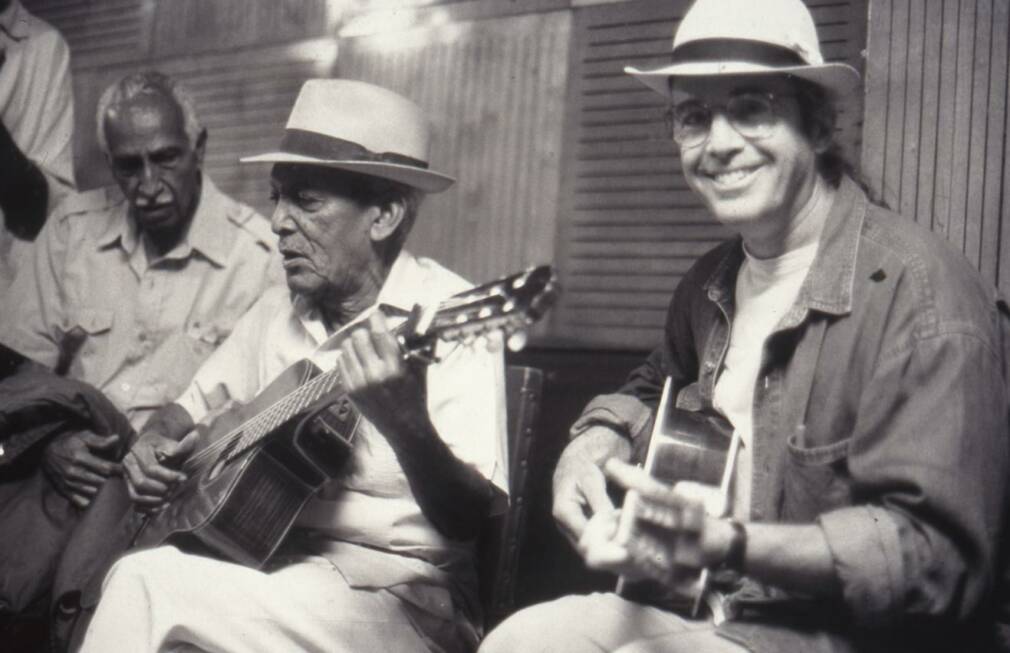

So we went and for the 1st week we recorded the Afro-Cuban All Stars album, which was quite a big band but with amazing rhythm sections, with Cachaito on bass, congas, bongas, maracas, a full rhythm session. 2 or 3 trumpet sections, saxophones, singers… I already knew that the Africans couldn’t come so I started to think “what do we do, for the 2nd week?”. I fell in love with “Guajiro”, the trumpet player, and Ruben Gonzalez as well. Juan de Marcos proposed that we keep some of these musicians. So we finish this big band album, and then in the 2nd week Ry arrived, then Eliades came in and we had the studio with the rhythm section, Eliades, Ruben, some of the singers, but the tape machine didn’t work. We had to get another piece of the tape machine from Mexico. Anyway… so we just had a room of these musicians and we had a day of just everybody playing and then working in the studio. And then Ry brought in this technique of using the microphones very high in the studio to get the sound of the room. Because he noticed early on that that room, the Egrem studio, sounds beautiful. You’d walk around the studio and it’s a big room. So we walk over here and Eliades would be sitting and playing some amazing guajira from Santiago, with a guy next to him playing congas, you’d walk a bit further and you’d hear Ruben playing some amazing bolero on the piano. So all of these little pockets of things were happening. And then that first day as well, Ry said he’d been told that there was an instinct musician called Compay Segundo that we should try and find. He must have been 80 years and.. something. So Marcos brought Compay who promptly arrived and said “I can’t record for you because I just signed with Warner Brothers two weeks ago”. So then we had to try and speak to Warner Brothers in Spain to ask permission. And then, we just started recording.

What repertoire?

The first song we recorded was “Chan Chan”. So… we started recording “Chan Chan” and then Compay said “I can’t record, because I haven’t got my permission yet from Warner Brothers”. So that’s why on the “Chan Chan” record, it’s just Eliades and Ibrahim, no Compay. Because he was afraid to sing without a contract. And I think the guitar solo is from Eliades as well, because Compay was afraid. But you could hear him in the background, he couldn’t resist. Anyway, eventually we got his papers sorted and then he was on board.

But also, it must have been on that same day, we were doing a bolero. And Puntito was singing it with his hard declamatory voice. And Ry said “can we find someone with a softer voice to sing this?” I only learned this recently but apparently outside, Barbarito said to Juan de Marcos “Get Ibrahim”.

– Ibrahim, the guy who used to sing? Juan asked.

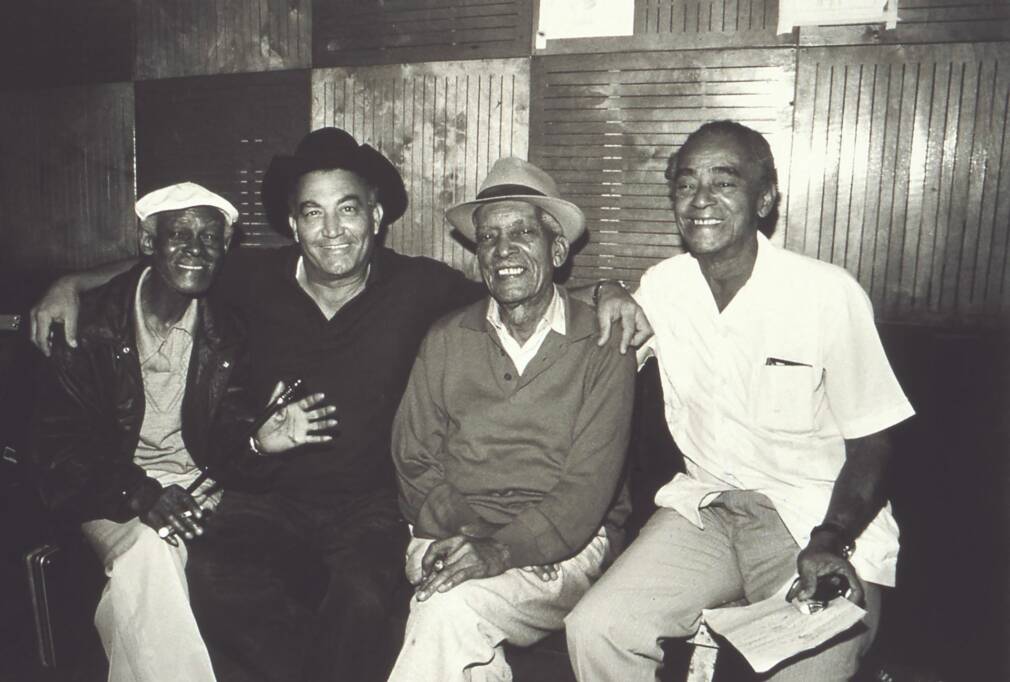

– Yea, he can do this stuff.

So Marcos went to Ibrahim’s house and realized Ibrahim didn’t want to sing anymore. He had an unfortunate time in the industry and didn’t want to sing. But Marcos persuaded him to come to the studio, and he came to the studio that morning – already the studio was fairly crowded with people, and it was a very amazing atmosphere because there were a lot of musicians who had retired, who weren’t working, who were meeting each other again. They would have known each other on the scene for years and years, but it was a sort of weird reunion. The atmosphere was very exciting and up and nice.

And was it your purpose to gather all these musicians?

No, not specifically. I mean part of that was an inheritance of Juan De Marcos’s project. From the Afro-Cuban all stars, he had brought in Puntito, Ruben, Cachaito, so he brought in a lot of older musicians. And Ry asked for Compay, as he was very interested in that sort of repertoire, the very old repertoire that people had forgotten. And Compay knew that repertoire. Barbarito said he’s a Bible, he knew all of that repertoire. And it became apparent that this was the sort of repertoire and style that was being looked for and those musicians played it best. Eliades was really young, compared to the other musicians, but he played that music in the same style that they did. He was an absolute brilliant practitioner of that music, of Santiago style.

Going back to Ibrahim… You got in and it was his first time in the studio for years?

Yeah, it was the first time he’d been in the studio for years, and he didn’t know what he was coming into. Marcos had just said:

– I need you to come to the studio.

– Okay, I’m coming in a couple of hours, Ibrahim had answered.

– No, they need you now !

So I think he quickly washed, put on a shirt and came down to the studio and as he walked into the studio Eliades recognized him because they are both from Santiago. I’d never heard of Ibrahim. Eliades started to play “Candela” and Ibrahim started to sing. But I didn’t hear this, I was in the room, watching; but he was brought in to do this bolero, so we said “do you know this bolero?” and Ruben started playing – it was Dos Gardenias. And Ibrahim sang, and everyone was just like open-mouthed, it was just amazing, it was just perfect. Especially for Ry, it was exactly what he was looking for. But you could see all of the other musicians as well, were like “wow, this is really something”. Because he wasn’t known as a bolero singer, Ibrahim, he was known as an up-tempo Santiago improvising singer. So I think it was sort of… a bit of a secret, that this is what he could do, and that was really what his love was, doing that music. He became a real star and focal point of the whole thing.

And what about Omara Portuondo?

Yeah, Omara would’ve been the most famous of all of the musicians we had on that session. I told you about Celina Gonzales before. So I wanted Celina to be on this project, Marcos wanted her to be on that project. I said to him:

– I’m having troubles with Celina, what is it?

– The shells, he answered.

– The shells… what’s the shells?

– I’ve got problems with the shells…

So we waited a couple more days. I asked again:

– Have you got any news from Celina?

– Hmm… the shells…

We went to her place and asked her again, and what she meant by “the shells”, she was trying the shells. To see how they were. So she was like asking the Gods whether she should do it or not. And they said not to. And it was amazing because she wouldn’t be persuaded. So… she didn’t do it.

Anyway, we had no woman singer, and I didn’t know Omara, she was supposed to be traveling, but we were in the studio, and there was a studio downstairs and Ry saw her, and he said, “get her, now, bring her up.” Marcos said:

– Omara, come!

– No, I can’t, I’ve got one hour, I’m going to travel.

– No, please come.

So Omara came up the stairs and we asked “can you record?” and she said:

– I can’t, I’m going to Vietnam to do a concert.

– Oh please, just…

Compay was there, and he said:

– Come on, let’s sing “Vente Anos.”

She went, sat next to him, they worked out something, amongst themselves, really quickly, and then they just played the song, one take, bam. Finished. And it was just amazing.

And that’s the one on the album?

That’s the one. It’s not just the one on the album, but the mix is the same, that’s the rough mix. Whatever you heard down, we played it right the next day and it was just beautiful. So when we were mixing the record, we just didn’t… and then we found the tape of the original rough mix of when they actually did it. And we couldn’t improve it, so that’s what’s on the record, yeah. And then she left. So that’s why she’s only on one song of the record, because then she had to leave.

The Buena Vista Social Club 25th anniversary edition is out via World Circuit.